“His paintings are realistic, not idealistic or romanticized, yet they offer an idea of the ideal life for humanity based on reason and the world as it actually is primordially, not based on ideologies or religious myth populated with supernatural entities such as God, Christ, angels, and the devil and his minions. Philosophically, his idea of the good life not only for individuals but for humanity as a whole is similar to that of the philosopher Epicurus. But philosophical discussions of the good life can’t compare to Homer’s paintings that allow us to see the good life as it is. However, I do think viewers miss that in Homer’s paintings if they fail to consider what his paintings mean beyond what they describe.”

“You mean that his painting express a philosophy of life.”

“Yes, though from what I read, he refused to discuss his paintings.”

“I suppose I understand, but did he say why?”

“No, but for me each painting is an oracle that reveals something important and mysterious about reality. But it’s left up to the viewer to figure out what that revelation is.”

“And religion doesn’t play a role in his paintings?”

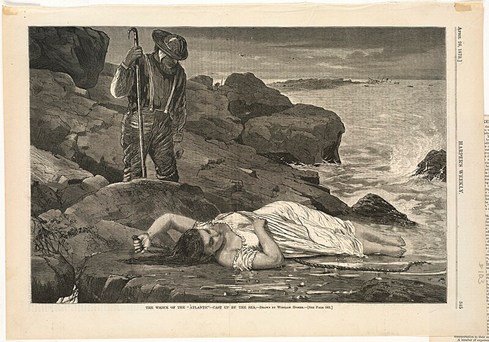

“I found no hint of religion in his paintings. There are school houses but no churches that I saw. Of course, true believers will interpret his paintings symbolically just as they do nature in order to find supporting references to their religious beliefs. Three of his paintings that I find relevant to the topic of religion are The Life Line, The Wreck of the Iron Crown, and Cast up by the sea.

The Life Line shows an unconscious female passenger being rescued from a stricken ship.

The masculine rescuer’s face is hidden by the woman’s red scarf, but we see the rough seaman’s hand of his arm that keeps the woman from falling off the small rescue seat attached to a rope by a pulley over a raging sea. The rescuer seems to be holding on for dear life with one of his boots in the water. The painting is significant because it too reveals the same primordial elements: femininity, masculinity, and the sea representing the destructive chaotic side of reality.”

“But what most viewers would see in the painting is a heroic man saving a damsel in distress.”

“That’s right, and there is nothing wrong with such an interpretation. It’s literal and matter of fact and even shows the important role of men as protectors of people in distress. Apparently Homer witness both incidents describe in the Undertow and The Life Line. As you said, that was also what the Civil War was about. But also keep in mind that the man is not identified as an individual, only his role as a rescuer.”

“But the woman is?”

“Yes. Seeing her as an individual makes the rescue more meaningful. She doesn’t just represent an idea. She’s a person.”

“But to you she represents an idea as well.”

“Very much so, which strangely the critics missed, or at least the masculine critics. Sadly they focused on the sensual characteristics of the woman, and it is true she is physically sensual—feminine soft rather than masculine muscular. But the critics focused her bust and thighs and even compared the two to a French painting called The Lovers, and I thought that was to be expected from critics saturated with the French sensibility and seemingly unlike Homer having had little experience of the real world that fascinated him.”

“But it is love in a way.”

“Exactly, but not sensual. It’s a higher love, a love of life represented by the woman. The love Jesus showed toward women. If there is one amazing aspect of Jesus’s thinking it is his ability to suspend masculine desire in his relationship to women.”

“Do you think Jesus was gay? Some people think so.”

“No. What Jesus does is what Plato recommends. He disallows the sensual desire to determine his thinking about women or people generally and perhaps even his emotions.”

“But love must have been present when he defended woman.”

“I think so. It's the love expressed in Homer’s painting The Life Line.”

“A higher form of love.”

“Yes, and given our discussion I must ask if Jesus’s altruism was motivated by this higher form of love or determined philosophically by the intellect.”

“I don’t know. What I can say is that the purest expression of altruism in the New Testament is Jesus’s parable of the Good Samaritan, which seems to be the ideal of moral behavior that Jesus set for himself and others.”

“What makes it so special?”

“We’ve discussed Kant’s philosophical approach to morality. Basically, he, like Plato, believed reason should guide our moral behavior.”

“Kant’s principle of autonomy.”

“Yes. Kant believed that logically there can be no morality without that principle, and so do I.”

“Because it demands that people’s autonomy be respected as long as they respect other people’s autonomy. That makes a lot of sense really. But it’s motivated by reason rather than altruistic love.”

“You got it. And that’s where Jesus takes morality a step further than Kant’s moral theory. Kant isn’t arguing for altruism. Actually, his principle of autonomy is a sufficient foundation for a social morally.”

“I see that. For one thing it prohibits all crimes involving aggression.”

“It does.”

“But for Jesus it wasn’t sufficient.”

“Apparently not.”

“What’s the difference?”

“The altruistic characters of the Bible—Ruth, Jesus, and the mythical Good Samaritan—seem motivated by love, not moral principle. For Kant, again like Plato, emotion is an unreliable foundation for knowledge thus a fallible guide for behavior.”

“Not everyone is loving.”

“Clearly not. So what Kant sets out to do is to find a moral principle that is universally reliable.”

“Which is what the principle of autonomy is, at least as far as I can tell, but bad people don’t care about morality one way or another.”

“That is the Achilles heel of morality.”

“And Homer’s painting The Life Line?”

“You tell me.”

“Clearly the rescuer is acting altruistically. And though I haven’t seen the painting, I would say his motivation wasn’t rational but love, the higher love Jesus represents”

“I agree. The rescuer loves the woman, and perhaps his motivation is greater because she is a woman, but he would risk his life in the same manner to rescue a man.”

“And that makes him a hero.”

“It does. And the critics who focused on the sensuality of the woman missed all that.”

“They weren’t philosophers.”

“They didn’t have to be. Ordinary people would see the rescuer’s heroism as an expression of a higher love without philosophy.”

“But you're a philosopher, so there is more to the painting than a heroic man risking his life to save an unconscious woman.”

“I speak not as a philosopher but as a retired merchant seaman who read philosophy books while at sea.”

“Whatever! You’re my philosopher.”

“Then I’ll do my best. You’re right. For me she is a lifeline to living meaningfully. Homer’s paintings are divided between the masculine and the feminine. Men are shown primarily at work, which is meaningful and necessary and at times inspiring. The grim side of masculinity is shown in his his Civil War paintings, as would be expected. Those paintings tend to be dreary. Rainy Day in Camp is one that shows soldiers gathered around a campfire.

In the background are tents, a row of tethered horses, and a blueish sky. The painting is colorful and wonderfully detailed yet the scene remains lifeless, ironically so given the number of men and animals. A forlorn looking mule expresses the tone and significance of the scene. War puts on hold the life celebrated by Homer—women and children and men performing useful tasks that contribute to life and its preservation rather than to its destruction. The scene is passive, but when the men and horses go into action it will be to kill other men. Homer’s paintings don’t celebrate war as a glorious enterprise and soldiers as idealized warriors. His view of war and its participants is expressed in a painting title Sharpshooter. The painting shows a sniper sitting on the branch of a tree. He looks though a telescopic scope for an enemy soldier to shoot. He is depicted doing this in a cool, calm businesslike fashion. The business of war is killing, thus an enterprise counter to all that Homer values as an artist. For Homer war is a tragedy, not something to celebrate. The sharpshooter illustrates the grim character of warfare, a business that engages in mass murder.”

“Is that how you felt when you were a soldier?”

“I didn’t do much thinking as a soldier. I recognized that the killing was necessary and that was about it. The killing and destruction were morally justified because the Allied Forces were fighting the aggressor nations that started the war and would conquer us all. We were doing what the rescuer in Life Line is doing. We were rescuing civilization from anti-life forces. Of course at the time I didn’t think in those terms. Nevertheless, we were participating in a necessary evil, not only the killing of evil men but also destroying cities and by doing so killing women, children, and other civilians. War is a grim enterprise. And important to our discussion of war, it’s necessary to recognize that war is no more an aberration of human behavior than a sea storm is an aberration of the sea.”

“You mean it’s natural.”

“History seems to say so.”

“That’s unpleasant, something I would like to know more about, but I must ask if your role in the war was like both that of the sniper and that of the rescuer in the Life Line.”

“Good point. I would say yes. The men I fought with were good men engaged in an enterprise that was not immoral nor wanted by them. Their sacrifice was both good and heroic, but did require loathsome behavior that dragged the men into a primeval discord that reduced them to worse than beasts. To me the war dragged humanity back to the Stone Age. And there was no escape. One became a beast in order to fight beasts.”

“So what were the revelations of the two paintings?”

“The two paintings show two roles, perhaps the two sides of masculinity, one associated with preserving life, the other with destroying life, anti-life really.

“And the woman in the Life Line painting represents life.”

“To me she does. Her red scarf indicates that. She represents everything associated with domesticity, and I don’t mean just taking care of the home but family life in general, including the domesticity of creatures, which is their ultimate purpose in life—to produce life and to sustained and protect the life they produce.”

“But creatures also take life.”

“To kill is not their primordial motivation. It is necessary to accomplish their primordial task, their preservation as a species .”

“To provide for and protect their offspring and other members of the herd or pack.”

“I don’t think most creatures are aggressive by nature. Their aggression is motivated to achieve some benefit—such as food, females, and defense. Humans are rather unique in their valuing aggression for itself own sake, even going so far as creating cultural forms such as religion and art that celebrate aggression.”

“Men primarily.”

“Yes. We consider masculine aggression as normal. Not so for women. Certainly not for Homer.”

“And his paintings show that?”

“They show women working in fields. In the paintings of soldiers there are no homes, fields, children, or communities. War cuts men off from all that. Thus, war cuts men off from life as a primordial value. Their role becomes that of the raging sea in the Life Line painting. Even nature becomes irrelevant except as an obstacle or benefit to killing the enemy or avoiding being killed by him. War can change one’s perspective on life. Furthermore, the female represents beauty, whereas there is no beauty in the image of a sniper in a tree or of dead soldiers, which apparently Homer never painted.”

”And you would agree.”

“That's one of the lessons I learned from my experience in the war. There is no beauty in death and destruction. Perhaps the wise Mr. Sage knew that Homer’s paintings would be especially meaningful to me because of my war experience.”

“We were discussing religion and you mentioned three paintings having to do with the sea. We’ve discussed only one, but not in the context of religion but in terms of masculinity and femininity.”

“You do have a good memory. And those painting were...?”

“The Life Line, The Wreck of the Iron Crown, and Cast up by the sea. You said Homer makes no specific references to religion, but apparently you find a connection in those paintings. So how are they connected in terms of religion?”

“Okay, I think I’m back on track. We see in The Life Line a man rescuing a woman, who without his aid would drown. Being young, sensual, and pretty she represents one of the primordial glories of life. The painting is saying that without her there is no life, which is clearly depicted in the war paintings of men waiting to kill. The Wreck of the Iron Crown shows about a dozen male rescuers risking their lives to return to the ship to rescue a single sailor who had been left behind. And the painting Undertow shows two men rescuing two half-drowned women.

“You mean the value of men isn’t inherent?”

“It’s primordial but still a choice. Life itself has inherent value, but I’m speaking of primordial gender roles. Both men and women can become artists, scientists, and doctors, but the primordial role of men has been that of protectors and providers, sustainers of life, which requires action, whereas the primordial value of women is their association with life itself. Homer could have used men or even children instead of women being threatened by the ocean. But then the painting would have lacked its primordial significance in terms of masculinity and femininity. And the woman represents beauty. Clearly, Homer considered beauty as an absolute value. The task of men should be to preserve life and beauty, not to destroy them. But it is not inherent. They must choose how to use their masculinity, to be protectors or destroyers.”

“As they do in war.”

“Yes. In war they fight either as protectors or aggressors.”

“From what you say, Homer was a big fan of women.”

“Certainly his paintings say as much. He saw women in a way we don’t seem to anymore. Most are pretty and even beautiful, some sensual, but he never presented them as sex objects. In that regard, Perils of the Sea is the painting of his that best expresses his adoration of women.

It shows two worried women standing on a pier looking out at a stormy sea. A group of men stand below them. One is pointing, most likely to a fishing boat in distress. The men are rescuers and the women are waiting for a loved one. What can’t be seen is the boat that is at risk. To me, the women are symbolically two Marys.”

“Mother of Jesus and who else?”

“I was thinking only of the mother of Jesus but we could include Mary Magdalene. The women are concerned about the men on the boat, perhaps husband, boyfriend, brother or father. What struck me is that the women are dressed in blue, the color associated with the Mary.”

“And what does their wearing blue mean?”

“That femininity is sacred.”

“Then Christianity got it wrong.”

“By worshiping masculinity rather than femininity?”

“Yeah.”

“As a primordial, masculinity never proved itself worthy of adoration. And when it is, it’s always in a destructive sense.”

“But Jesus wasn’t destructive.”

“No, but those who worshiped him were.”

“Do you think Homer saw women in that way?”

“His paintings seem to say so.”

“And men?”

“They are praised, not adored. In Perils of the Sea the two women are not associated with sensuality but with the primordials of love, family, and life. They are also sacred because love, family, and life are what the men at sea risk their lives for. Nothing else.”

“That way of viewing of women is a lot different from how they are presented today in magazines, movies, and music videos today.”

“Very much so. His way of understanding women is similar to the way the ancient Greeks did. How ironic that Greek statues of naked women, goddesses but human women nonetheless, are not erotic.”

“I agree, though some men would see them in that way.”

“Simple minds, yes.”

“Why aren't those statues erotic?”

“I think, though I’m not certain, it was because they were not to be understood in the context of sex.”

“As women are today are.”

“A change that is rather recent, at least in America. Until then, Homer’s view of women was the norm in America. Yes, there were saloon gals to entertain the lonely men of the Wild West. They performed a necessary niche role on the frontier, the outskirts of civilization populated mostly by unmarried men. But being a saloon gal wasn’t the role of women celebrated by the country’s culture. And it may be the case that these temporary female companions were not looked down upon as sex objects by the men who appreciated their company. I say that because I don’t believe the country was as obsessed with sex as it is today. In fact, even rather recently Hollywood produced movies that continued to venerate women as sublime beings.”

“Which movies?”

“Sam Wood’s Our Town and Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront.”

“Who were the women?”

“In Our Town Emily Webb and Edie Doyle in On the Waterfront.

”Sorry but I don’t know those movies. I didn’t go to the movies growing up and my dad watched only westerns TV.”

“That’s understandable. The movies are old. But if your father is a fan of westerns you might have seen My Darling Clementine.”

“Oh yeah, more than once. And Clementine is the woman.”

“Yes, and Chihuahua, a hot-tempered but lovable saloon gal who isn’t presented as a sex object in the movie. She loved by Doc Holliday. And those depictions of American women are very similar to Homer’s. But by the time of On the Waterfront came out in 1954 that view of women had pretty much disappeared from American culture. A cultural paradigm shift occurred.”

“I understand that they were traditional icons of femininity. You see that in the many of the paintings of other artists such as Singer Sargent, George Caleb Bingham, Mary Stevenson Cassatt, and Elizabeth Nourse. But what was lost in the transition?”

“I think it comes down to the disenchantment of femininity. The women of the Greeks and of Homer are enchanting for two reasons. Beauty made them supernatural but not in the religious sense but because beauty is subjective thus transcends materiality. Second, they possessed the ability to bring life into the world, which was to older cultures quite mysterious, as it should be. Thus, women were linked to life, beauty, home, family, tribe, and the continuation of a culture. The Greeks recognized the role of women as sacred, again not necessarily in the religious sense. In fact, it seems that the ancient Greeks, along with other pagan cultures, deified the role of women by inventing goddesses to represent them. And that had to give women status that would make it difficult to view and treat them merely as sex objects, which really is a trivial way of viewing and treating women.”

“So what happened?”

“Judaism for one. The Jewish religion celebrates masculinity, not femininity. Goddesses were reviled and banished and replaced by a deification of masculinity—Yahweh. That Greek statues of goddesses were defaced by Christian mobs illustrates the Abrahamic religions’ hatred of the feminine as does their masculine God Yahweh, shown by his cruel treatment of the plucky ingénue Eve. With Judaism women fell from grace. They became servants of masculinity rather than the other way around.”

***

“And Homer's painting The Return of the Gleaner can help us understand the female-nature relationship because it shows the gleaner to be at one with the natural world that surrounds her.

And he must have considered that relationship to be profoundly meaningful because it shows up in many of his paintings, including The Gulf Stream.”

“Okay, I’m curious. You must explain that relationship.”

“I would love to. I’ll use The Return of the Gleaner because Homer uses symbols to express that relationship.”

“That would be great, but before you do I must ask why Homer’s paintings are so personally important to you, because they clearly are.”

“I was surprised by how deeply they spoke to me. I love his paintings because they are enchanting and because I agree with what they say about the human relationship to the Earth-world. Perhaps it’s also a bit of nostalgia.”

“For when you were young.”

“For a way of life that preceded even my own. A time and place that was of Homer’s, one he celebrated.”

“But you believe he knew the world was changing—becoming modern.”

“Most thinkers of the nineteenth century knew that. I don’t see how he couldn’t have known. I believe that knowledge must have partly inspired his paintings, but I can’t say for sure.”

“He paints a way of living that is precious and irreplaceable, yet lost in time.”

“Nicely put.”

“It’s odd how your thinking is so modern yet you’re really not a modern man.”

“Christine, you should have been a psychologist rather than a painter.”

“No. I’m too much like you and Homer for that. Besides, I find it difficult managing my own life.”

“But you’re right. I’ve lived a modern life in a modern world. I grew up in a modern city, fought in a modern war, lived aboard modern ships. And in a way I didn’t give my world much thought until I started reading.”

“And Homer’s paintings spoke to you about another way of living, another way of relating to the world?”

“They did. They spoke to me of a world I never knew and wish I had. You know I’ve never had the opportunity to discuss Homer’s paintings with someone until now. Not even with Mr. Sage. And I do enjoy talking with you. I know that you will agree with my appreciation of Homer’s work because you too are an artist.”

“Still, I learn from you what I didn’t learn in art classes.”

“In what way?”

“Your interpretations are more philosophical and less technical. More than that, having lived in the wild lands of New Mexico I know something about the world appreciated by Homer. The world you call primordial. But let’s not drift away from your analysis of The Return of the Gleaner.”

“Then let’s begin. What I see in the painting is a primordial unity between the woman and nature—not simply in the fact that she is a peasant doing agricultural work. First of all, the rhythm of her work is determined by her physical relationship with the nature, not by the requirements of a machine. She holds a hay fork, which is a tool, not a machine. The difference is important. The hay fork doesn’t separate her from the wheat in the way a tractor or combine would. More symbolically, the woman’s head scarf is the same shape and color of the clouds. Her blue apron is the color of the sky, and it and her dress are stirred by the wind as is the wheat in the field. So to me the painting says she’s as much a part of nature as are the clouds and wheat.”

“Do you think viewers would see that?”

“If that’s what they’re looking for or sensitive to. They would if they were of the frame of mind that allowed them to see the unity of the woman and the rest of nature. The female-nature relationship is pretty universal.”

“So you’re interpretation sees the painting from a gestalt perspective.”

“I think so. Otherwise, the focus of the evaluation would be on the significance of the woman. She is front and center and her feminine presence dominates the painting. One could argue that she is a symbol of fertility inherent in nature.”

“A Demeter figure.”

“Exactly, and there is a paganistic quality to many of Homer’s paintings.”

“No references to Christianity?”

“Not in the book I read or in the paintings of his that I saw. There are country schools but no churches. I believe his worldview is contrary to Christianity, which considers humans essentially spiritual beings radically separated from nature. Whereas for Homer farmlands, pastures, forests, rivers and the sea are people’s primordial the settings, Christianity divides the world into the natural and the supernatural and the two are considered incompatible. The proper dwelling place for humans, at least mentally, is the supernatural experienced by going to church, reading the Bible, or praying. Eve turned away from the supernatural when she was drawn to a tree in nature. For that, the Bible has her punished. Christian morality demands separation. The First Epistle of John says, ‘Love not the world, neither the things that are in the world. If any man loves the world, the love of the Father is not in him. For all that is in the world, the lust of the flesh, and the lust of the eyes, and the pride of life, is not of the Father, but is of the world.’ The flesh world is the material world. Thus, the Christian worldview is totally incompatible with Homer's.

From Frank Kyle's unpublished The Girl and the Philosopher.