The infected aren’t the only predators in the story. There are also men who are cannibals who would most likely eat Ellie after raping her. Joel is the typical masculine hero whose job it is to protect not only a female but a child in a world overrun by monsters of one kind or another—a world not so unlike ours, especially if one lives in a society in the thrall of masculine aggression such as Ukraine. Joel does his job—killing infected monsters, evil men who aren’t infected, and even the medical personnel who seek to sacrifice Ellie as Agamemnon scarified his daughter Iphigenia and as Abraham would have sacrificed his son Isaac on God’s say-so. Joel refuses to allow Ellie to be sacrificed for the greater good, even against Ellie’s wishes. It is his absolute commitment to her that makes him a hero to the fans of the game. The game has many similarities with 1883. Joel embodies characteristics of both James Dutton and Shea Brennan, and Ellie’s role in the story is similar to that of Elsa’s.

At

the end of The Last of Us 2 Ellie

ends up alone and depressed in a world still filled with evil monsters and evil

men, but with no one to love and protect her. Her hero is dead. The emotional motif of

the first The Last of Us was love,

just as love is the dominant motif of 1883.

The emotional motif of The Last of Us 2

is hatred. I never played the sequel because doing so would be like repeatedly watching

Laszlo Toth hammering away at Michelangelo’s Pietà. Instead I relied on game reviews such The

Last of Us Part 2 Is Worse than You Think by Zaid Magenta and The Last of Us Part II - Angry Review by

Angry Joe. Both are on YouTube and are extremely insightful and entertaining.

What is revealed by the two episodes of The Last of Us is that misandric feminism is simply another us-versus-them ideology of hatred. What is most interesting about The Last of Us 2 video game is that the viewer can see the negative transformational effect an ideology can have on a story or society. The tone and mindset of the second game is totally different from the first. And unlike Top of the Lake the second game doesn’t offer a hero or a workable solution for dealing with masculine evil. In Top of the Lake an evil man is killed by the story’s female hero. In The Last of Us 2 the hero is killed and the murderer is allowed to escape. Thus, The Last of Us 2 is as nihilistic as Grand Theft Auto games. Its negativity gives nothing to believe in, whereas the first game gives a realistic scenario for how to confront evil but more importantly a way of life infused with love that inspires protecting that which is most important in life represented by Ellie as it is represented by Elsa in 1883. She gives Joel’s life primordial meaning that is worth living and dying for.

In Top

of the Lake there are three categories of evil men. The first and largest

are the knuckle-draggers. These are brutes whose Stone Age DNA is impervious to

humanizing cultures. (They do exist.) The second group is the police force which

is made up of male pedophiles and rapists who target young girls or any other

females. As cops they represent the idea that men are not to be trusted even

when they wear uniforms that say they can be trusted. Then there are the

miscellaneous male scumbags that look harmless or even pretend to be friends

but will rape a woman who drops her guard because she is too trusting.

Apparently that happened to Detective Robin Griffin, which would explain her

chronic depression.

The

focus of the story is Griffin’s investigation of a twelve-year-old girl who

tries to commit suicide and later runs away into the forest. She had been

repeatedly raped apparently as a victim of a pedophile ring run by cops. Young

girls are drugged and offered as sex toys for a price, of course. (Such

organizations do exist in the U.S. but they’re not run by cops, though they might be ignored by some cops for a price.) Nature is a better

place than any place populated by men if only because nature, though harsh and even deadly, is honest.

I recall 20 year old Cara Evelyn Knott who was raped and murdered by police

officer Craig Alan Peyer, in San Diego, where I lived at the time. At the trial

it came out that he had made predatory sexual advances on multiple female

drivers. His uniform said “You can trust me.” But he couldn’t be trusted and

used his uniform as a ruse for unsuspecting women. And who would they report Peyer

to, the cops? Not the women. Still, one dirty cop doesn’t mean all cops are dirty.

However, the Top of the Lake logic of the misandric feminism is as follows:

The

fallacy of assuming all men are bad because some men are bad is called the

fallacy of composition. The problem for women is that some bad men can give the

impression that all men are bad or at the very least cannot be trusted. And the

rape statistics for the U.S. is 16% of women have been victims of rape or attempted

rape. In his book The Non-Suicidal Society

Andrew Oldenquist argues that that an indication of societal breakdown is the

increasing inability to predict the behavior of other members of the society

toward oneself. In such a society a woman who finds herself among men may perceive

all of them as potential threats. My own view is that women in the U.S. have to

view men they do not know with cautious suspicion.

I sound as if I agree with the misandric feminism of Top of the Lake. I don’t. Misandric feminism is a categorical condemnation of all men. In the series, there is simply no room for good heterosexual men. The only two good men are a gay and a Māori. The male heterosexual European offspring are all bad. That is the view of New Zealand men presented by the series. What is puzzling is that New Zealand ranks 7th in U.S. News and World Report’s “Best Countries for Women.”

Other

countries are Sweden, Norway, Finland, Denmark, Switzerland, Canada, Netherlands,

Australia, and Germany—all European. What makes these countries the best

countries for women? The answer is complex, involving the legal and political

systems and the culture. However, one reason has to be that the men of the

countries want women to have the same rights and opportunity as they do and to be safe and

happy. In Top of the Lake men are for

the most part rotten and it is a woman cop who achieves justice. But in the

real world women alone are incapable of creating best countries for women

without the help of men. And there are many such countries in the world. Of

course, a misandric feminist's utopia would be no male inhabitants, represented

in the series by the Paradise cult.

Top of the Lake hardly offers inspiring women. There

is the Paradise cult of women who live in railroad cars. They are damage

merchandise who seek to separate themselves from the world. When the sun

shines, they play nudist camp. The rest of the time they do group therapy led

by a woman named GJ who calls the women on their delusions but has nothing else

to offer. How could she when she, so it appears, has given up on life. They

have no purpose in life beyond themselves, kind of like the Eloi in H.G. Wells’

The Time Machine except they are all

women. The detective seems as if she is on Prozac while pursuing her case.

Visuals of her face suggest that she is chronically depressed. Other than her

case, she doesn’t have a life. I don’t count as a having a life having occasional sex with a former boyfriend who apparently set her up to be raped. And her mother didn’t press

charges against the men who raped her daughter, and being Catholic she force

her daughter to give birth to the offspring of the man who raped her. Okay, she

has good reason to be depressed. For women, religion is of no help at all.

Most likely the woman would be condemned as a seductress. Watch The Magdalene Sisters, a compassionate

film written and directed by a man Peter Mullan.

The

tonality of the series is similar to film noir, dark and depressing without

beautiful women and handsome men or a hero. Is the detective a hero or just

wants revenge against those who raped her? Perhaps that doesn’t matter, but

what does matter is that I expect movie heroes to be inspiring and the detective

is anything but inspiring. She’s dreary like the entire series. What about rape

victim Tui? She becomes feral creature living in the forest. She is a survivor,

not a hero. Movie heroes should be inspiring.

Sigourney Weaver as Ellen Ripley in Alien

and Aliens is massively inspiring. In

the the second film she is devoted to saving a young girl. She too is

disillusioned by masculine evil in the form of corporate evil. Then there is Emily

Blunt as a FBI agent in Sicario (also by Taylor Sheridan). She

encounters masculine evil that ranks with the Xenomorphs Ripley has to contend with.

And Linda Hamilton’s Sarah Connor of Terminator

2: Judgment Day. These three characters/actresses are inspiring. I don’t

fine Elisabeth Moss’s detective inspiring or even realistic. She has her

moments. At times she looks silly wearing a gun too big for her. And the chronic

frown doesn’t help. She is a depressed personality that is inconsistent with an

inspiring hero. I’m certain that in real life are many heroes—male and

female—who are depressed (dealing with evil people would be depressing), but

we’re talking about movies. Watching Top

of the Lake is like reading the obituaries. Hardly inspiring.

I

see two problems with Top of the Lake

that have to do with its misandric feminist ideology. First, the traditional

source of meaning—boy meets girl, the two fall in love, marry, have children—is

out of the question because a boy is involved. In addition, feminism sees

marriage as a trap for women, a way for men to get free a live-in maid, cook,

and sex toy. A good novel that explores the issue of domesticity being a trap

for women is Kate Chopin’s The Awakening.

In the novel Edna Pontellier wants to be an artist. In the story art—painting

and music—offer a meaningful option to domesticity. In Top of the Lake the only option offered is to become a cop hunting

down evil men. Its theme seems to be women are trapped by masculinity. Even the

rescued Tui must face, as did cop Robin Griffin, giving birth to the child of

the man who raped her.

The first epic based on a

journey was the Mesopotamian The Epic of

Gilgamesh, followed by Homer’s Odyssey.

But unlike the events of those two poems, the American westward movement was a

historical epic; thus, epic status came naturally to western stories about wagon

train journeys. Raoul Walsh’s The Big

Trail was the first and perhaps the best until 1883, which is significant because the transition from the male

protagonist (John Wayne’s character Breck Coleman) to the female as the central

protagonist (Isabel May’s Elsa Dutton) involved a leap over a thousand western

movies. What makes the American western epic unique other than being based on

recent events is that it is about the heroic struggle of ordinary men and

women, not larger than life Homeric and Arthurian superheroes.

Bazin’s characterizing the

conflict of the western as Manichean is of interest. Three religious ideologies

that see the world as involved in a supernatural cosmic conflict between the

forces of good and the forces of evil are Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, and

Judeo-Christianity. That view of reality continues to remain popular among

Christians who believe the forces of Satan are at war with the forces of Christ.

It was the other two religions along with us-versus-them Judaism that

caused Christianity to adopt the “us-versus-them” cosmic war scenario.

The two founders of Christianity are Apostle Paul and Augustine of Hippo. The latter had been a Manichean before converting to Christianity, and his Manichean thinking—along with Paul’s war of the spirit against matter/flesh—greatly influenced negativity of Christianity. Historian Charles Freeman says in The Closing of the Western Mind, “It was Augustine who developed a rationale of persecution” (295) and that “Augustine’s rationale for persecution was to be used to justify slaughter (as of the Cathars or the native people of America” (Freeman 299). Except for his mother, Augustine was also a woman hater, most likely an attitude he adopted from his mentor Apostle Paul. Thus, after becoming a Christian he sent away the mother of his son. Manicheaism also found its way into Marxism with the global conflict between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie.

Bazin believes that the best western movies capture the mythic conflict (with and without the religious context), and they are unique for doing so with a popular genre. Good versus evil is a central theme in the ever popular gangster movies and in film noir crime stories. However, these two popular genres never achieved mythic status, and the reason for that, I believe, is location. Crime movies take place in the confines of cities, whereas westerns take place in the great outdoors, the “immense stretches of prairie, of deserts, of rocks to which the little wooden town clings precariously (a primitive amoeba of civilization)” (Bazin 145). To know what Bazin means, one must visit Monument Valley:

Raoul Walsh's The Big Trail included locations such as the Grand Canyon, Yosemite, and the giant redwoo

Atomized people swirl about

like atoms in cities, and the conflict between good and evil isn’t cosmic but one

involving criminals, victims, and cops. There is no journey or quest. The

series Naked City open with this

line: “There are eight million stories in the naked city.” Lots of little

stories but no big story. A city like New York City has mythic proportions but

its stories do not. To be fair, the best crime stories do emphasize the larger

than life presence of the city, but the characters themselves are not involved

in a mythic conflict, perhaps because there is no goal beyond survival. Another important difference between big-city crime stories and the western is the preponderance of people in the big-city and the comparative absence of nature—landscapes; lakes, rivers, and streams; arching sky; and plants and animals. In a sense, cities are prisons that cut their inhabitants off from nature. The natural environment—in particular wilderness—has a mythic character without the need of narrative. Nature has mythic presence. Naturalists such as Edward Abbey and Ansel Adams recognized nature’s mythic character. So does Elsa.

What Bazin Gets

Wrong

Bazin missteps when he says,

“The (1) Indian, who lived in this world, was incapable of imposing on it man’s order. He mastered it only by identifying himself with its (2) pagan savagery. The (3) white Christian on the contrary is truly the conqueror of the new world. (4) The grass sprouts where his horse has passed. He imposes (5) simultaneously his moral and his technical order, the one linked to the other and the former guaranteeing the latter. The physical safety of the stagecoaches, the protection given by the federal troops, the building of the great railroads are less important perhaps than the (6) establishment of justice and respect for law” (145).

What

Bazin gets right historically is that the Christians conquered the new world with guns, germs, and steel.

He uses the word “conquered” as if the conquest was a good thing. For white

Christians it was. For the Indians it was a disaster. And ditto that for South

America and Canada. Number (4) implies that nature rejoiced in response to the

invasion. Tim Flannery’s The Eternal

Frontier offers a different view, describing deforestation, the shooting

into extinction passenger pigeons, the population of which was 3 billion to 5

billion, and the shooting almost into extinction the bison, with 30-60 million bison reduced to

about 675. That’s a lot of killing. And the killers were all men.

Trees were also hit hard by

pioneers. Less than 4% America’s original forests remain in existence, most in

protected public lands. That’s a lot of cutting. So, I don’t think nature

rejoiced at the arrival of the Christian conquerors, who showed no restraint in

their conquest of nature because the Book of Genesis told them that nature was

given to them as a commodity, not as an object of reverence which only God

deserved: “God blessed them and said to them, ‘Be fruitful and increase in

number; fill the earth and subdue it.

Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature

that moves on the ground’” (1:28). And they did just that. Of course, the

decimation of the native people was included in the conquest. They belonged to

nature, not to God, and would be treated as such. Like the ancient forests they too live on reservations protected by the U.S. government.

(3) Thus, Bazin is correct when

he says, “The white Christian on the contrary is truly the conqueror of the new

world.” Here comes the irony, offered by another wagon-train story How the West Was Won. The French title

is less euphemistic: La Conquête de

l'Ouest. Bazin calls such westerns “superwesterns.” I call them Cadillac westerns—bloated with mega-famous movie stars. It’s disappointing to see that

John Ford, inventor of the lean mythic western, took part in the project. But

Hollywood has the Midas touch. The irony comes at the end with the film with an

epilogue narrated by Spencer Tracy that shows how modern America grew away from

that vision of creating a bucolic paradise with images of Hoover Dam, a

four-level downtown freeway cloverleaf interchange in Los Angeles, and the

Golden Gate Bridge. The hoped for pastoral paradise became the technological

nightmare depicted in Godfrey Reggio Koyaanisqatsi.

“The (1) Indian, who lived in

this world, was incapable of imposing on it man’s

order. He mastered it only by identifying himself with its (2) pagan savagery.” The wisdom of the

Native Americans was learning how to live in harmony with nature. Nature is primordial

reality, and as Leonard Susskind points out, humans mess with nature at their

peril. The Indian world might have endure a few more thousand years had the

white man not showed up with his advance technology—in particular guns—and

unlimited religion-fueled hubris. It’s problematic that modern civilization

will finish the present century without being disrupted by nuclear warfare or a

catastrophic climatic shift.

Apparently, Bazin knew little

to nothing about the way of life of Native American pagans. Their goal was

never to impose man’s order on nature. That concept would have been foreign to

them. Their goal was to live in harmony with nature, which they believed they

were a part. It was not until reason became a tool of masculine aggression did

the assaulted on nature occur in earnest. The mastermind was Francis Bacon. He

rationalized the Genesis project of subduing nature. According to Carolyn

Merchant, Bacon saw nature as feminine, adding another justification for the

assault. She says, “Due to the Fall from the Garden of Eden (caused by the

temptation of a woman), the human race lost its ‘dominion over creation.’” The

idea here is that nature became like Eve—inherently unruly. Thus, says Bacon, “she

[nature] is [to be] put in constraint, molded, and made as it were new by art

and the hand of man; as in things artificial.” To quote Merchant, “’By art and

the hand of man,’ nature can then be ‘forced out of her natural state and

squeezed and molded.’ In this way, ‘human knowledge and human power meet as

one’” (The Death of Nature, 170).

More accurately, masculine

reason and power become one and impose themselves on nature in a manner

justified by God. Only a God that is supernatural (existing outside of nature) could command that nature to be subdued. The pagans—demonized by the masculine

minds of the Abrahamic religions—worshiped deities inherent within nature; thus

any attempt to subdue nature would be an affront to the gods and would result

in tragedy for humans. The Hopi word Koyaanisqatsi

means life out of balance. I believe

that is an accurate description of the modern world. Today’s world is not

totally out of balance but is moving in that direction. Unlike the ancient

peoples, technological man has the power throw the world way out of balance.

This is actually suggested in 1883 with its references to the Civil

War which killed over a half million Americans. The killing took four years.

Today, a nuclear bomb can kill that many in a matter of minutes. Masculine aggression

existed among Native Americans, but their weapons killed each other one at a

time, not thousands in the blink of an eye. Two archaic a-bombs killed a

hundred thousand Japanese in minutes. (MIRVs are missiles that can carry up to

10 nuclear warheads! That’s progress?) An estimated total of 70–85 million

people perished in World War II, about 3% of the 2.3 billion people on Earth in

1940. Both the atomic bomb and the war reflect modern man’s ability to create life-destroying

disorder. Also, of interest is that the human population went from 2.3 billion

people in 1940 to 7.8 billion people today. I don’t see that as an indicator

that world is moving toward a more orderly state. As the Native Americans

discovered in 1883 more people can

result in an increase in disorder. Big cities seem to indicate that as well. In

1883 Fort Worth is a dangerous city

full of dangerous men. Today, the city’s crime rate is 40% higher than the

country’s average. Americans completed the conquest of the west just seven years later (1890), and

look at the country now—a paradise only when compared with secular and

religious totalitarian states. About two million jailers, detectives, security

guards, and cops are needed to keep order. And still 16,425 people were

murdered in the country in 2019. That's more than double the

Thus, Bazin’s complaint about

pagan savagery rings a hollow as does his claim (5) that the white Christian “imposes

simultaneously his moral and his technical order, the one linked to the other

and the former guaranteeing the latter.” The two World Wars, the Vietnam War,

the Iraq war, and the Russia war against Ukraine are just a few of the more

recent examples that prove white Christian nations are quite capable of

immoral, savage behavior. And it started 1,700 years ago with the first

Christian Roman emperor Constantine I. Here is how Ramsay MacMullen describes

the man so beloved by Christians: “The empire had never had on the throne a man given to such

bloodthirsty violence as Constantine” (Christianizing

the Roman Empire: A.D. 100-400, 50). The Abrahamic religions are notable

for their ability to exacerbate masculine aggression simply by divinely justifying

aggression. Of course, the masculine will to power plays a central role in all

three religions. The epiphanic irony of Judaism is that Yahweh “himself”

illustrates the masculine will to power.

In the context of the feminism

of both Top of the Lake and 1883, this carnage indicates that men

are the problem. Yet, they are also the only realistic solution to the problem,

which Top of the Lake ignores and 1883 recognizes. However, we know that good men fighting bad men is only a stop-gap solution. The best solution for

everyone would be for all men to control their propensity for violence. And both

series seem to conclude that solution is wishful thinking given masculinity’s incorrigible

aggressiveness. However, 1883 does

suggest that the best solution resides with women—though it can be realized only by good men. Women will have to inspire men to recognize that what women

represent is humanity’s primordial value—a celebration of life and nature

rather than violence, death, and destruction. Women such as Elsa Dutton (and

others) are able to inspire good men to protect women, children, and community

from bad men. However, if masculine aggression is an absolute as both series

imply, it is problematic and perhaps wishful thinking to believe that bad men

can ever be inspired to be good men.

There have been many cultures

that considered women, children, and community the primary value of human

existence because they are the primordial values of existence. God is an invented

value, abstract and otherworldly in the sense that unicorns and mermaids are

otherworldly. They are simply not a part of Earthy life in the way nature’s

creatures are. In addition, all the Abrahamic religions introduced a

demonization of women that did not exist among the ancient Greeks and Native

Americans. Those religions corrupted the cultures of the ancient Greeks and

Native Americans that respected women and by doing so protected women against

masculine aggression. Yes, the lack of respect leads to aggression toward women.

Luther Standing

Bear says, “The woman of the household had no ‘lord and master’ when it came to

deciding where she and her children were to live.... The furnishings of the

tipi home were all the handiwork of the women. Women and children were the

objects of care among the Lakotas.... A man’s family was his first thought” (Land of the Spotted Eagle 83 & 91).

About the treatment

of children Vernon Kinietz says about the Huron in The Indians of the Great Lakes: 1615-1760 that “Punishment of no

kind seems to have been used, the children growing up in complete liberty. This

condition and the resulting small show of respect for their parents shocked

Sagard [Gabriel, a missionary], Champlain, and others” (92).

The same is

illustrated in Deloria’s Waterlily.

So, what did Native American societies have and didn’t have that created a

culture in which women and children were safe from masculine predation (except during warfare), which is not the case for many so-called civilized

societies as indicated by both Top of the

Lake and 1883? First of all,

though Native American children’s showing “small respect for their parents”

does not mean they didn’t respect their parents and other members of the tribe.

It means that they were unruly as children often are. They learned to respect

(have admiration for) their parents and other members of the tribe by observing

them. This kind of relationship between parents and children is clearly

illustrated by independent-minded Elsa’s relationship with her parents and

other adults such as Shea Brennan and Thomas.

Second, Native American cultures did not encourage children to disrespect their parents and other adults, as Hollywood-dominated American culture has been doing for decades. On the other hand, American adults encouraged being disrespected as illustrated by white adults’ treatment of blacks in the South during the Civil Rights movement and by the idiocy of white politicians (Kennedy, Johnson, et al.) who sanctioned the Vietnam War, drafting 58,220 young American men of all colors to their deaths and killing a million or more Vietnamese men, women, and children. Here is an image of a Vietnamese child severely burned by napalm:

Native American

cultures were culturally and morally far more restrained toward other people

and nature than American culture has ever been. Rules of behavior came from the

culture itself and the people, not from an authoritarian book or authoritarian

males, such as Texas judge William Adams’ who alludes to the Bible as he

viciously beats his disabled 16-year-old daughter, Hallie. One reference was to

Paul’s Ephesians 6:1: “Children, obey your parents as in the Lord.” The judge

was simply following the advice of Proverbs 13:24: “Those who spare the rod of

discipline hate their children.” (The video is available online.)

This is an excellent example of how the Bible can be used to condone violence by transforming cruel and vicious acts into an expression of love. Abraham would have sacrificed his son Isaac out of love for God. And let’s not overlook the Bible’s sentencing to death homosexuals: “they shall surely be put to death; their blood is upon them”(Leviticus 20:13). Thus, it’s okay to kill homosexuals because God says it’s okay. And in Texas Adams did no wrong because “The Texas Penal Code states [with biblical consistency] that the use of non-deadly force against a child is justified if the person using force: Is the child's parent or stepparent,” etc. Native Americans were without the Judeo-Christian Bible that condemns women as inherently sinful and says that use of violence is acceptable if God gives permission as “he” gave LBJ and George W. Bush permission to go to war.

This is how religion leads do moral nihilism by having God-centered ethics overrule human-centered ethics. Of course, men are the ones who decide what are God's ethics. However, even if God “himself” condemned to death homosexuals doesn't mean the condemnation is ethical. God's flooding the world and destroying cities were immoral actions. When God is placed above human morality, morality becomes nihilistic because any action can be justified by claiming God condoned it—such as the extermination of pagans, members of other religions or no religion, and heretics like Jesus.

Masculine

aggression was still present but directed toward enemy tribes and animals that

needed to be killed for food. What was most importantly absent from Native

American tribes was a hate-filled deity that created enemies where none existed

before. Women are condemned from the very beginning of the Bible with the

condemnation and punishment of Eve—a negative view of women that that would

continue with all the Abrahamic religions, but truly reaching an apex with pinnacle

with Apostle Paul. This hated of women illustrated by the murder of pagan

philosopher Hypatia by a mob of Christian men. She was, according the Abrahamic

religions thrice damned: first as a pagan, second as a woman, and third as an

educated woman who was infinitely more intelligent (as a philosopher,

scientist, and pagan) than the men who murdered her.

Native Americans

had enemies, but no enemies created by an ideology. There was no condemnation of people as infidels or heretics for what they believed or did not believe. Ramsay MacMullen and Catherine Nixey tell us

in Christianizing the Roman Empire

and The Darkening Age: The Christian

Destruction of the Classical World, respectively, how Christian religious

ideology tore the empire apart. The titles are misleading. The conflict was

between Roman citizens, those who converted to the Christian religious ideology

and those who wanted to remain pagan until they were forced to either convert

or die.

Christianized Roman

pagans simply did what Jesus wanted them to do: “I have come to set a man

against his father, and a daughter against her mother, and a daughter-in-law

against her mother-in-law. And a person's enemies will be those of his own

household” (Matthew 10:35-36). Family and tribal members turning against one

another was unheard of among the Native Americans. The Greek city states fought

one another but not over ideology. In her book The Greek Way Edith Hamilton says that in Greece there was no

dominating church or creed. She said religious persecution was so slight in

Greece that it would not have been considered had Socrates not been its last

victim (175 & 181). Ditto that for Native Americans. Another kudos for

Native Americans is that they possessed no slaves, whereas the Bible condones

slavery. Runaway slaves were adopted into Native American tribes. In 1883 Christian (I assume) Elsa becomes

betrothed to Sam, a Comanche, a pagan warrior.

I believe the best

of all possible worlds for women and children can be created from elements of

ancient Greek and Native American cultures—both pagan. One big obstacle is the popularity

of the religions that hate pagans, infidels, and heretics and condemn women as

inherent sirens of corruption. The origin of this notion is Eve’s so-called

corruption of her boyfriend Adam because she didn’t want to hang out with a dummy.

The ancient Greeks and Native Americans offer cultural elements out of which a

civilized society in which women and children are safe and respected can be

constructed. A society that doesn’t respect women and children and endangers

them is at best less than civilized, at worst barbaric.

There are two

obstacle that to creating a civilized society—the origin of both being

masculinity. The first are the masculine knuckle draggers that appear in both

series. The society itself may not be the problem but an abundance of men who

act as predators toward women and children. If a society falls under their

influence, it becomes criminalized beyond the salvation of good men. How should

such men be dealt with? Both Top of the

Lake and 1883 suggest

termination. According to Immanuel Kant’s foundational moral principle of autonomy, the lives of

people should not be interfered with unless

those people violate the principle—by aggressing women or children. If they do,

their moral right to autonomy is rescinded.

However, if the

obstacle is an ideology that defines the culture, then the civilizing process

encounters an insurmountable obstacle. The idiocy of George W. Bush’s nation

building project show showed that much. The problem here is that aggression

breeds aggression in its most destructive form—war. The U.S. has tended to use

war as a political tool to get what it wants. Wars consist of invaders and

defenders; the actions of the former are immoral and the actions of the latter

are moral. Simply illustrated: invading a home is immoral; defending one’s home

is moral. And, of course, the men who invade are immoral and the men who defend

are moral. Also, helping a neighbor to defend his home is moral in the Good

Samaritan sense (altruistic), as in the case of helping Ukraine defend itself

against invading Russians.

Thus, the best

responses to nations that are defined by inhumane ideologies do not include

aggression except to defend one’s own nation and other humane nations against

aggression. Having friends is essential to surviving in a world constantly

threatened by masculine aggression. The first response is to isolate evil nations. One

justification for this is moral—again Kant’s principle of autonomy. The other is

practical. Nations that are evil because they have succumbed to some form of

aggressive-oppressive masculinity must be tolerated not because they are good

but because interference in the form of aggression could very well end up being

evil.

The unfortunate

lesson here is that some evil nations must be tolerated as long as their evil

remains within the nation’s borders. Attempting to save the nation from itself

could very well result in a greater evil being committed by the so-called

liberating nation. However, a response that does not involve invasion and war

is isolation. Civilized nations should shun uncivilized nations as much as

possible. However, greed and humanitarian fanciful thinking often results in

benefiting thus empowering evil aggressive nations—such as Russia and China.

China hasn’t invaded Taiwan yet, but most likely will in the future because

that is what masculine aggression--unrestrained by morality—does. Thus, the

only reasonable and moral response to nations ruled by oppressive masculinity

is isolation and preparation, with the hope that change will come from within.

Which might be wishful thinking given aggressive masculinity seems as absolute

as gravity. It is interesting that both the Russian and Chinese revolutions

simply replaced one masculine authoritarian government with another. Ditto that

for the overthrow of the communist regime of the USSR. After the demise of

Stalin the communist regime seemed almost civilized compared to the mad man now

in control of the country.

In 1883 we watch Elsa struggle to live the

life she wants for herself against conventional demands represented by her

mother and her aunt, Claire Dutton. In part, the wide-open spaces (being away

from the restraints of social convention) not only allow her the freedom to realize her life as she wants but offer her options rooted in the organic world

of nature. Thus her self-realization has primordial depth that it would not

have in a society defined by an artificial ideology. To a certain degree that

goes as well for men. William Blake sums up the natural life contra the

artificial life in the poem “The School Boy”:

Like Elsa, the school boy finds nature sweet company.

Why? Because nature is his primordial origin and doesn’t impose artificial

restraints on his life. He wants to be in nature for the same reason people go

camping and hiking in nature—to get away from the structure society imposes on

its members. It is also a return to the primordial world, the mysterious and enchanting

Earth-world that gave birth to mountains, valleys, deserts, plains, rivers,

lakes, oceans, rain, clouds, wind, snow, and all the creatures we share Earth

with. Nature is our primordial home. In Top

of the Lake 12-year-old Tui finds safety in nature away from masculine

predators. It is also a place of freedom and openness rather than the

organized, confining space of a city or a school room. Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi shows the transition from the primordial natural space

and time to the artificially created space and time in which life becomes

externally regulated. According to Koyaanisqatsi the city is a

grid-like structure similar to a computer chip that totally organizes life.

In western movies

the open spaces of nature are associated with freedom. This mental and physical

space is celebrated by the scenes of Elsa riding her horse. The desire for

greater freedom is represented by the German immigrants in 1883. Of course, greater freedom comes with risks. Space and time

are rationally organized for the purposes of productivity and safety. Bridges

are built so rivers can be safely crossed. Outlaws seek to escape the law and

order associated with a civil society. Society is a process of using reason to

organize time and space and people so that they are more easily managed and less threatening.

But as Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi shows, unbridled

rationalization of space and time produces the technological city that can harm

people in other ways. A topic addressed by Robert Wright in his Time magazine article “20th

Century Blues.” The problem is illustrated in 1883 by the city of Fort Worth where Elsa almost gets raped. So it

seems the pastoral paradise of the story is ever elusive. And the town and

country divide has some relevance to feminism if one considers the city to be

the product of masculine reason seeking to control time and space whereas the

time and space of nature is considered feminine, occurring naturally. Watch Koyaanisqatsi with attention to reason’s

geometrical transformation of space and its quantitative compression of time.

In “The School Boy” the school house can represent the city, the teacher government and bureaucracy, the books and learning social conditioning or indoctrination in extreme cases. What the school boy wants is what Elsa briefly achieves and would have had for a lifetime had violent masculinity not taken her life. Returning to Elsa’s simple wisdom about eudaimonia or the good life: Being the in world and love are all that are needed.

In his The Spirit of Modern Philosophy Josiah Royce says about Schopenhauer that his “pessimism is actually expressive of a very deep insight into life” (229). Schopenhauer’s view of reality is that it is the product of an irrational cosmic Will that produced and infuses everything in the universe. He was inspired by Kant’s noumenon, the ultimate reality behind the phenomenal world that we live in. It is believed that ultimate reality is nothing like the reality of time and space that people live in that seems so rational in its design—at least as seen on Earth before the age of telescopes.

Kant’s philosophy

suggested that ultimate reality (the noumenon) was completely alien—beyond our

comprehension, more so than the Christian God, which is a ghostly humanoid, but because the human mind is

not designed to comprehend absolute chaos or absolute irrationality. Kant’s

philosophy along with everyday experience caused Schopenhauer to develop his pessimistic philosophy that understands the world we live in to be the product of blind,

irrational Will. In Royce’s words, it is a terrifying view: “that life is

through and through tragic and evil.” Elsa discovers that as we should have by

now. And both Schopenhauer and Royce didn’t believe that the tragic truth

should be annulled by creating an alternate divine reality that explains the

imperfections of life as the result of a mischievous waif in the Garden of Eden. And the solution to Schopenhauer’s problem, says Royce, “surely cannot lie in any

romantic dream of a pure and innocent world far off somewhere, in the future,

in heaven or the isles of the blessed” (232). That is the reality Elsa

encounters and must come to grips with.

Royce’s response to Schopenhauer’s pessimism and the reality that inspired it is relevant to masculine feminism—though no feminist himself: “I think that the best man is the one who can see the truth of pessimism, can absorb and transcend that truth, and can be nevertheless an optimist, not by virtue of his failure to recognize the evil of life, but by virtue of his readiness to take part in the the struggle against this evil.... If these men are brave men, their sense of the evil that hinders our human life will some day arouse them to fight this evil in dead earnest...” (231). Important here is the role that Royce sets out for men, illustrated in 1883. The series makes pretty clear that evil is an inherent problem that humans must face. This evil is natural, not supernatural. If it were supernatural in the form of Satan and his bad boys, then why would God allow it, as he allowed Eve to be conned by wily Satan? Why does God allow bad boy Satan to exist? Being invincible to pain, injury, and death, why doesn’t “he” do what good men do who are not invincible to pain, injury, and death—fight evil? The answer is actually pretty simple. God is an invented ghost in the machine.

The good brave men

that are needed are men like the good men in 1883. There are, however, two types of evil. The first is natural evil

that comes in endless forms from nature, which is as Galileo and Schopenhauer

reveal and Elsa discovers, far from perfect. Natural evil is “anything that causes

injury, anything that harms or is likely to harm.” But this evil is not immoral

or wicked because it lacks the intent to harm. That describes the other form of

evil—men who knowingly seek to cause harm. Such men are the greatest and most

disgusting threat to humanity. In a sense, their evil is natural because it is

rooted in their biological DNA, to which they choose to be slaves. That DNA

exists in good men as well, but they choose not to live as slaves of their DNA

but as Good Samaritans, that is, they choose to liberate themselves from their

bestial tendencies by choosing to live morally. Thus, morality—in this sense—is

a form of freedom.

Second,

Schopenhauer's solution to counteract the cosmic Will was for humanity to adopt

an attitude of resignation and passivity. He got the idea from the Orient—Hinduism

and Buddhism. Both are life-denying religions that focus on the afterlife. Essentially, it is the solution of the Lotus-Eaters in Homer’s Odyssey or Timothy Leary’s solution “drop

out and tune in with drugs” adopted by hippies. A person waves the white flag to

life by dropping out. Shakespeare puts the choice this way: “To be or not to

be? Whether ‘tis nobler in the mind to suffer the slings and arrows of

outrageous fortune, Or to take arms against a sea of troubles, And by opposing

end them…” (act 3, scene 1 Hamlet).

To passively suffer the slings and arrows of life is Schopenhauer’s selfish,

ignoble choice. “To take arms against a sea of troubles, And by opposing end

them” is Royce’s choice and the choice of the heroes of Top of the Lake and 1883.

For Schopenhauer

there was also losing oneself in the contemplation of art. Such an idea might

seem strange until one experiences the beauties of Paris—its woods and parks,

architecture and museums, in particular the Musée d'Orsay. As with the ancient

Greeks, the French know the transporting power of art, so did Schopenhauer. Yet

there is a sadness that comes with experiencing great works of art produced by

humanity. It comes not from knowing the imperfections of the world of nature

but knowing the imperfections of men. Just to think, Paris was almost destroyed

during World War II. How ironic that Paris was spared destruction by a Nazi—Dietrich

von Choltitz, “Saviour of Paris.” “Hitler did not completely give up on the

destruction, with the Luftwaffe conducting an incendiary bombing raid on August

26, and V2 rockets fired from Belgium, causing extensive damage” (“Dietrich von

Choltitz,” Wikipedia). And today Vladimir

Putin has threaten to send nuclear warheads to Paris and London, delivered by

his favorite new missile “Satan II.” The name is appropriate for Putin

as well. It seems that if evil men acquire enough destructive technological

power not even good men can prevent them from destroying civilization. I think

this is resonated in the killing of Elsa. Who’s the pessimist now!

Elsa also learns

the dark side of love in an imperfect world. Just as love pulls her out of her

depressing pessimism her beloved cowboy is murdered. From such a loss one

cannot completely recover. This is most clearly illustrated by Shea and her aunt

Claire Dutton. The loss of her cowboy lover Ennis create a hole in her life that

cannot be filled, just as it could not for Shea. That loss makes Shea a harsh

overseer, not out of bitterness but out of concern for others. Neither that

concern nor Shea’s altruism heals the wound caused by the deaths of his wife

and daughter. The role of Good Samaritan doesn’t give him a new life but only

purpose enough to continue to live, which was not the case for Claire.

Elsa finds love

again and in that love reason enough to continue living. However, she is no

longer the optimistic girl who began the journey. In this sense, the story is a

bildungsroman, a growing up or “coming of age” story. Elsa begins the story as

a child and ends as an adult having suffered disappointment and loss. Yet, her

journey is also shared by the audience who wants everything to work out for

Elsa and want a happy ending. But the audience, like Elsa, has to face the fact

that reality is indifferent to human expectations. With the loss of Elsa the

story shifts from being a bildungsroman to a tragedy. The ancient Greeks were

the first to understand that life is a glorious yet tragic affair. They

believed correctly that humans bring tragedy upon themselves unnecessarily by acting

unwisely. That type of tragedy exists in 1883.

But the tragic view of Taylor Sheridan’s 1883

goes beyond that of the generally optimistic Greeks who believed the world was perfect but humans weren’t. Let’s call it an

existential tragedy. Tragedy that is unavoidable in an imperfect world.

Judeo-Christianity

attempts to eliminate tragedy from life with a deus ex machina happy ending in a postmortem life. By doing so,

cheats Elsa’s death of its tragedy—with such platitudes as “She’s with Jesus

now.” No, she is simply gone. The loss of her life is absolute. There is no

getting around it except in memory—as Shea does. However, because she was cut

down in the youth of her life, memory of her bring more pain than joy. Her

death resonates though the entire story. That is the poignancy of 1883 and is why I will watch the series

only once. Yet, that is the purpose of 1883.

It is not only a return to the western but also a return to reality.

He is in deep despair at the loss of his wife. In his pursuit of power he lost that which he loved most. There are two important ontological observations in the passage. The first is that dusty death awaits all things. The Second law of thermodynamics says the same. Second, the all—the Universe—is a tale told by an idiot of sorts. The meaning is that it has no grand purpose. Thus, in the great scheme of things the Universe is full of sound and fury but signifies nothing. It is without purpose. As physicist Carlo Rovelli puts it in his book Reality is not What It Seems, “There is no finality, no purpose, in this endless dance of atoms. We, just like the rest of the natural world, are one of many products of this infinite dance” (9). The irony here is that he is stating the view of philosopher-scientist Democritus who revealed twenty-three centuries ago the truth of human condition in a world made up of atoms. It’s not surprising that he was known as the “laughing philosopher.”

The life of the ancient Greeks and Native Americans were equally demanding and hazardous or more so. And their mythologies don’t make them the purpose of the universe. Yet, both celebrated joyfully living in the Earth-world that did not celebrate them.

Yes, that is also the ontology of 1883. However, what we also learn from Elsa is that the ontological condition that humans are thrown into does not preclude humans giving it and their existence meaning. It is a hard world, but it is also beautiful and full of potential meaning that make one’s brief existence meaningful. That is summed up in Elsa’s beauty and loving nature. Beauty and love are absolute values that can give absolute meaning to life—as they do to Elsa and to those who know her. Her role in the film is to represent all that is good and meaningful in life. And instead of complaining that life is cruel and imperfect and leads only to death, she embraces the fullness of life—the good and the bad. And, as Shea notes, she lives fully during the brief time of her life.

Kant said that “God

is a useful fiction developed by the human mind” (Will & Ariel Durant, The Story of Civilization: Rousseau and Revolution 550).Yes, the fiction has had many

uses such as serving the wills to power of such men as Constantine I and

justifying men lording over women. It also has served as a palliative for what

Gilbert Murray calls in his Five Stages

of Greek Religion “the failure of nerve”—to face reality. So an artificial reality—a religious security

blanket—was created in which death need not be final. Elsa—like Schopenhauer—faces

reality as it is. She doesn’t allow grief, sadness, and disappointment to cause

her to lose her nerve.

Religion not only

cheats life of the tragedy but of its value. First of all, the invention of God

demotes the value of the material world—our world, the Earth world—the one we actually

live in, the world that sustains and entertains us and gives our lives concrete

purpose. The invention of God created an eclipse that cast a shadow over the

lifeworld because the invented God logically becomes the more important than

the world “he” supposedly created and manages. But Elsa chooses to live in the

realm of red-pill reality rather than in a blue-pill make-believe made from

words. She, like the school boy, prefers to be outdoors in nature surrounded by

mountains, fields, and forests. The loss of Elsa’s life is an absolute loss—as

seen in the faces of her mother and father and her friends. But the absolute

loss of her death reveals the absolute value of her life. Death is a more

honest teacher than a Christian preacher. It says value life, value existing in a world

that is as magnificent as it is terrifying. Death and her own heart are Elsa’s

teachers. She learns to appreciate life in the here and now while she can.

Without God life becomes an adventure. With God it becomes a tall tale with a predetermined end told by men who knew nothing about life because they lived in the house of religious myth, a house made of words without windows. Nuns are women who live according to the myth and escape from the world by confining themselves in convents. The houses are churches, mosques, and synagogues. But like the school-boy confined in a school house, Elsa prefers to live in the real world in spite of its dangers because she wants to live freely and truthfully. And she finds the real world to be a glorious adventure that reveals the multiplicity of its reality to the senses, the windows that open upon the world, rather than in words and the imagination.

The Bell Curve of Masculinity

Freud would characterize masculine aggression as a primary instinct of the most primitive part of the human personality—the id. It is an evolutionary weapon that evolved to protect and feed humans for most of humanity’s existence. It became encoded in the genetic makeup of men. A bell curve would categorize some men as violently aggressive, some not aggressive, and most falling in the middle range. Carl Jung would characterize the situation in terms of the anima (subconscious feminine psychological qualities) and the animus (subconscious masculine psychological qualities). Men and women possess both to varying degrees. Important here is that aggression in men seems to be a deadly absolute like gravity.

The

Bell Curve of Femininity

In the DNA bell curve of women,

aggressive women are a minority—though abuse and culture can cause women to act

inconsistent with the genetic tendencies. The German philosopher Martin

Heidegger became a Nazi because doing so served his will to power ambition. A philosopher

who would uncritically become a Nazi is a sham philosopher. Philosophy is

essentially a discipline of skepticism that is supposed to prevent thinkers

from succumbing to nonsensical claims (illogical, non-empirical), especially

those of religious and secular ideologies. In addition, philosophical ethics

would be especially critical of such claims when they encourage violence toward

others. However, most shocking is that his wife Elfriede also became an avid

Nazi. By doing so, she acted contrary to the genetic tendencies of women. She

became a Nazi before her husband did and remained a Nazi longer than he did. Rüdiger Safranski says in his biography of

Heidegger, Martin Heidegger: Between Good

and Evil, that as a party activist, she brutally mistreated women, having “no

scruples in ‘sending sick and pregnant women to dig entrenchments’” (387).

Judaism’s

Demonization of the Feminine and Deification of Masculine

Generally, the psychology of

women can be characterized as caring, compassionate, kind, and altruistic. The

Old Testament is a celebration of and testament to masculine aggression, but

occasionally the qualities of the female shine through, even at the very

beginning. The female Eve discovers a tasty brain-boosting fruit and the first

thing she does is share it with her boyfriend Adam. And aggressive masculinity

also appears in the first book of the Old Testament in God, aka Yahweh. The

most interesting thing about Yahweh is that “he” is pure aggressive masculinity.

In Genesis “he” punishes all of humanity with suffering and death because of

the behavior of the two youngsters who gave birth to the human species and

humanity’s first human, male murderer Cain—with whom God sided with after

Cain murdered his brother Abel.

Yahweh also causes an extinction event with a flood. "He" is supposed to be forgiven because "he" saved a boatload of humans and other creatures, but all the drowned humans and other creatures remained dead. "He" destroys cities full of people "he" dislikes (and children are unable to avoid the holocaust), and, as the rest of the Old Testament tells us, "he" found all of humanity except for his chosen people to be an abomination. And "he" often found them to be abominable as well. Later on, "he" encourages his people to carry out his wrath against the people "he" hates (pagan nature worshipers) by exterminating them and destroying and looting their cities. That looks a lot like what Putin is doing today. Even gentle Jesus gives into masculine aggression:

“Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth; I have not come to bring peace, but a sword. For I have come to set a man against his father, and a daughter against her mother, and a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law; and one's foes will be members of one's own household” (Matthew 10:34-36).

So,

if one wants to investigate masculine aggression, the Bible is a good place to

begin. Generally, the Old Testament doesn’t show much respect for women while

often praising the despicable behavior of the men—even the so-called great

heroes such as King David who had a loyal soldier Uriah killed in order to take

Uriah’s wife Bathsheba as his eighth wife. David’s son King Solomon with

a harem that included 700

wives and 300 concubines (1 Kings 11:3) makes Hugh Hefner look like an amateur.

Solomon wasn’t wise, just a dirty old female-molesting man. See Giovanni

Venanzi‘s painting King Solomon being led astray

into idolatry in his old age by his wives (1668) and note who gets the blame. Of course,

his real crime isn’t idolatry but unbridled lust that leads to the reification and subordination of women.

Really,

how many of those wives and concubines wanted to be part of his harem?

Question: Were the wives and concubines of David and Solomon in reality sex

slaves? King David’s treatment of ten concubines suggest the answer is yes: “When

David returned to his palace in Jerusalem, he took the ten concubines he had

left to take care of the palace [sex toys and maids] and put them in a house

under guard.... They were kept in confinement till the day of their death,

living as widows” (2 Samuel 20:3). And Christians believes Jesus is ennobled by

being a descendant of the line of David forever ruling in righteousness. David

was hardly a righteous man, in reality the opposite.

Ruth: The Embodiment of

Feminine Goodness

The Book of Ruth is a notable exception to the endless descriptions of the disgusting behavior of men in the Old Testament. Loving, devoted, good-girl Ruth is a big surprise in a very big book filled with hateful, aggressive, sex-obsessed, and often evil men like King David and his sex-addicted son. Ruth's altruism serves as a foil to the Old Testament’s central theme of predation. In story Ruth and Orpah of Moab had married two sons of Elimelech and Naomi. After the husbands of all three women die, Naomi urges her daughters-in-law to return to their families. Orpah does so, but Ruth will not abandon her mother-in-law, saying quite movingly, “Don’t urge me to leave you or to turn back from you. Where you go I will go, and where you stay I will stay. Your people will be my people and your God my God. Where you die I will die, and there I will be buried” (1:16-17). It’s significant that Naomi advises that her daughters-in-law return to their families. That the role of family in life is essential was considered axiomatic by ancient cultures. The importance of family in Native American cultures is beautifully described in Ella Cara Deloria’s Waterlily, which explores family life among Dakota (Sioux) Indians.

Ruth represents pure

selflessness. She isn’t worried about death but about her mother-in-law Naomi.

The painting Naomi with her

Daughters-in-Law by Henry Nelson O'Neil (1817-80) captures feminine love

and beauty. It’s noteworthy that the story and the painting illustrates that

life has profound meaning without God. The film 1883 illustrates that as well. Raphael’s painting Madonna in the Meadow shows that—unlike

God—women, children, and nature are tangible sources of meaning that inspire

love and appreciation. God exists only in words, and those words have had a

negative effect on how people treat one another.

In

addition, Ruth’s feminine altruistic, selfless human-centered ethics—motivated

by love—are superior to Yahweh’s hate-filled, God-centered ethics. I will add

at this point the altruistic ethics of the Good Samaritan. His ethical

motivation isn’t love but duty (but maybe love as well). Doing one’s duty is a

great virtue as long as it is altruistic—helping creatures vulnerable to

suffering. Good Samaritan altruism is also often illustrated in 1883. In the film we see that family has

a humanizing effect on men. It doesn’t feminize them so much as it gives their

lives a raison d'etre that is

motivated not just by duty but also by love.

Altruism in 1883

James

Dillard Dutton’s altruism is motivated primarily by his love for his family,

yet this love widens over time to include others. James is an important male

character because he is an instinctive killer. Bazin says,

“If it is to be effective, this justice must be dispensed by men who are just

as strong and just as daring as the criminals” (146). James is certainly that, but his family life repurposed his masculine killer

tendency to protect others. Shea Brennan seems primarily motivated by duty,

which he sees as convincing others to act prudently and wisely and in a

disciplined manner because not doing so results in tragedy, which it often does

in the story. The consequences of not acting prudently are illustrated early

the in the series. James shoots dead a drunk man who attempts to rape his

daughter (being drunk is no excuse for rape) and by Claire Dutton’s throwing

rocks at dangerous men with guns. Shea Brennan often expresses too harshly his

demands for sensible, disciplined behavior in part because he is a former

military officer, and the settlers are ordinary people, not disciplined

soldiers, as his friend Thomas, a former soldier and slave, has to remind him.

However, his concern for others seems to be rooted his love of his wife and

daughter. He fears that the settlers’ lack of discipline will bring disaster

upon them, and it does. However, duty is

not an inherent good: duty to good is good; duty to evil is evil.

A Good Woman Isn’t Hard Find

In

my long life I have met many good men and a few bad men, some capable of evil

behavior. I have also met many women—family members, colleagues, friends,

lovers, and acquaintances. Each was, in her own way, beautiful. Yes, as 1883 illustrates with Claire Dutton some

women can be meanspirited, angry, and verbally abusive. However, Claire’s

mean-spiritedness most likely resulted from having lost six children and

apparently a husband. Endless hardships and disappointments can make the best

of people angry and spiteful. I’m arguing that Claire’s negativity didn’t come

naturally but as a result of having lived a life of hard knocks and

disappointment. When a group of masculine thugs ride into camp she unwisely

throws rocks at the leader causing the men’s barely repressed masculine aggression

to flare up. The men murder a number of settlers including Claire’s daughter. Still,

as the series indicates with other women, Claire’s negative thinking and

behavior are an aberration. The other women in the series are kind, caring, and

compassionate.

What

I am claiming is that 1883 is an

example of masculine feminism, a feminist perspective expressed by a man. This

is more than moderate philosophical-political feminism because it is an

expression of love—if you will—for women. The writer of the series is Taylor

Sheridan, and given its feminist (feminine is a more precise word) themes I

believe it can be considered an example of masculine feminism. He is married to

Nicole Muirbrook and she might have been an influence on his thinking about

women. Before 1883 he showed

masculine feminism in his movie Wind

River, which depicts the aggressive behavior of evil men toward a Native

American woman and the role of the masculine hero to seek justice.

Though

Sheridan returned to the traditional western, he did so with greater emphasis

on the significance of the female presence. The traditional western portrays

the conflict between good men and evil men in which women play a passive though

essential symbolic role (Stagecoach, Shane, and My Darling Clementine) representing love, marriage, family, school,

and church—masculinity's raison d'être.

Nevertheless, they receive greater value than Mary does in the New Testament. Mary—the

so-called mother of God—is a minor character in the New Testament. She is

mentioned by name twelve times in the Gospel of Luke, five times in the Gospel

of Matthew, once in the Gospel of Mark, and once in the Book of Acts. Judaism

and Christianity played a dominant role in marginalizing the value of women in society.

In a sense, Sheridan returns to the valuation of women by pre-Christian

societies such as that of Native Americans and the ancient Greeks.

The Feminine Inspiration for

1883

It

is said that Isabel May was Sheridan’s inspiration for 1883, an inspiration that recalls Dante being inspired by Beatrice

to write the Divine Comedy. (See the

painting Dante and Beatrice by the

artist Henry Holiday dated 1883.) The Divine

Comedy is a journey among the dead. Entering into the realm of the dead is

the central theme of Judeo-Christianity—not life. Elsa Dutton is the central

figure of 1883. Hers is a journey

into what she represents—life—in all its complexity, beauty, enchantment, possibilities,

successes, failures, euphoric moments, and ultimate tragedy, not death, though

death is ever present.

The Haunting Presence of Death

and the Glory of Life

Contrary

to what Christianity would have us believe, death is nothing to look forward to. It is the end of all that is good,

sublime, and wonderful—all bundled in the character Elsa Dutton. Unfortunately,

that is also why Elsa must die—to remind us to appreciate (and protect) life

while we are alive. Elsa’s role in 1883

similar to the female in Eugène Delacroix’s painting Liberty Leading the People. However, what Elsa represents is not

leadership or liberty (yes a little of the latter for women) but the raison d'être for human existence,

especially for masculinity. She represents glorious femininity. She is

beautiful in the way nature is beautiful. Her beauty is organic, not

artificial. She inspires love and returns love—as a lover but also as a child

and friend. Her loss as a lover, child, and friend is terrible. The film is

designed in such a way as to make her loss unsettling to the viewer. Elsa’s

story deeply depressed my wife who is a mother of a daughter and granddaughter.

Elsa’s Haunting Death

The

death of Elsa reminds one of the Marabar cave incident in Forster’s A Passage to India. Poor Mrs. Moore hears that terrifying

echo: bou-oum ou-boum. Everything exists, yet nothing has absolute value. All

had emerged from a dunghill created by the Big Bang. She wanted there to be

more. Poor little talkative Christianity, she thought. In that echo, as in

Elsa’s death and the death of her beloved cowboy, humanity is stripped of its

guise of transcendent, eternal value. Her death embodied perhaps the most

painful truth of human existence: that ultimately nothing lasts and nothing

matters in the great cosmic scheme of things. (This is the central theme of literary naturalism,

which 1883 echoes.) That is the hard

lesson Elsa learns. With her death it becomes a tragic lesson for the viewer as

well. Yes, she has loved and valued, but she was denied fulfilling her love and

self-realization. And it was not only her pain. Her death shakes to the core of

the being those who survive her. At her death, Shea Brennan attempts some

consoling words—true and wise—yet they cannot bring Elsa back nor fill the

terrible emptiness caused by her absence.

There

is no consolation except perhaps that of having known her. It is a loss that

was experienced by Shea when he lost his wife Helen and daughter to smallpox. As accustomed

as he is to loss, he too is traumatized by Elsa’s death. The film reminds us

that loss is a universal, inescapable part of the human condition—of everything

really. To express this aspect of the human condition the ancient Greeks invented

tragedy, which is essentially what 1883

is. As the film shows, there is no escaping the tragic side of existence. It

comes to everything. And thankfully Sheridan

doesn’t try to soften tragedy with religion. There is in the film no indication

that the dead are on their way to a glorious afterlife. They are buried in the

dirt, to which they will return; then they will be forgotten once the

generations that knew them are also gone.

Death

is not evil. Men who cause unnecessary death are evil. That is the hardest

lesson Elsa has to learn. Death is not evil because it is the very nature of

reality that everything that exists must come to an end. The stuff that makes existence

possible is unable to preserve that which it creates or even itself. Physics

tells us that the primordial stuff out of which the cosmos and its inhabitants

are made will deteriorate and dissolved into nothingness. Democritus believed

his atoms were forever. They’re not. The word “atom” means cannot be cut, but

they can be cut and are by atom colliders. Thus they, like everything else, are

composites that disintegrates and disappear. Even our magnificent

planet—Earth—will be killed, ironically by that sustainer of life the Sun.

Unlike Christianity, the Greeks

Loved Femininity

Like

Taylor Sheridan, ancient Greek civilization was one that was very much inspired

by women. Their art, in particular their pottery and sculpture, along with

their numerous goddesses testify to their love of the feminine. Homer’s Iliad is about a war fought over a

woman. And his Odyssey is about the

journey of one of the war’s heroes, Odysseus, who seeks to return home to his

wife the faithful Penelope, who is being assaulted by mischievous suitors.

During his journey he encounters notable females such as Helen, Nausicaa, and Circe.

Of the greatest importance is that for the Greeks women were to be celebrated, not

condemned, as they are by Judaism and Christianity.

According to those religions, a single woman—a girl really—was the cause of all of humanity’s problems—a female Pandora’s Box. In the New Testament Jesus spends a good deal of his time protecting women from abusive Pharisees. The Pharisee who was the most hateful of all toward women was Apostle Paul. He never mentions Mary in his letters. In addition, he was a hater of the flesh, which he considered inherently sinful. He associated women most closely with sinful flesh:

“Live by the Spirit, I say, and do not gratify the desires of the flesh. For what the flesh desires is opposed to the Spirit, and what the Spirit desires is opposed to the flesh; for these are opposed to each other, to prevent you from doing what you want” (Gal 5:16-17).

“If you sow to your own flesh, you will reap corruption from the flesh; but if you sow to the Spirit, you will reap eternal life from the Spirit” (Gal 6:8).

Like the invention of God, the invention of the spirit demoted the material Earth-world. All matter is despicable flesh to spirit worshipers like Paul. Spirit is pure no-thing. Actually, however, sowing the flesh produces children, not corruption. But Paul had little use for children. All he can say about them is, “Children, obey your parents as in the Lord” (Ephesians 6:1).

He also tells slaves to obey their masters: “Slaves, obey your earthly masters with respect and fear, and with sincerity of heart, just as you would obey Christ” (Ephesians 6:5). American slaveholders would use the passage to justify slavery. And, of course, he tells women to obey their husbands: “Wives, obey your husbands as you obey the Lord. The husband is the head of the wife, just as Christ is the head of the church people” (Ephesians 5:22-23). Husbands are the lords of the family and women are their vassals. What is clear here is how Judeo-Christianity is used to religiously justify masculinity’s oppression and exploitation of others.

For the Abrahamic religions, rooted in Judaism, obedience is everything. Whereas in 1883 freedom and children are celebrated. The immigrants seek to escape the oppression of their homeland and Thomas is a former slave. Elsa’s father encourages freedom rather than discipline. Her mother is more of a disciplinarian but her motivation isn’t loyalty to God but to Elsa’s welfare. Jesus wasn’t much better than Paul. He says,

“Let the little children come to me, and do not hinder them, for the kingdom of God belongs to such as these. Truly I tell you, anyone who will not receive the kingdom of God like a little child will never enter it.” And he took the children in his arms, placed his hands on them and blessed them. (Mark 10:14-16)

Again

it’s all about God, not the children themselves—who are an inherent value

associated with the female. His message is twofold: (1) do not hinder the children

from embracing my religious ideology, and (2) adults accept my religious

ideology as obedient children. There is no ideology—religious or secular in 1883. The bountifulness of life is all

you get, and it is more than enough to people like Elsa who experience life with

appreciative awareness. And children are one of the primordial values of life

as Elsa and her brother John Dutton illustrate.

Artists—not God-centered religious ideologues—reveal most movingly the importance of women and children. Let’s begin with Raphael Madonna of the Meadow: mother, children, and nature are all that really matter in this painting. All the religion gets is a stick in the shape of a crucifix:

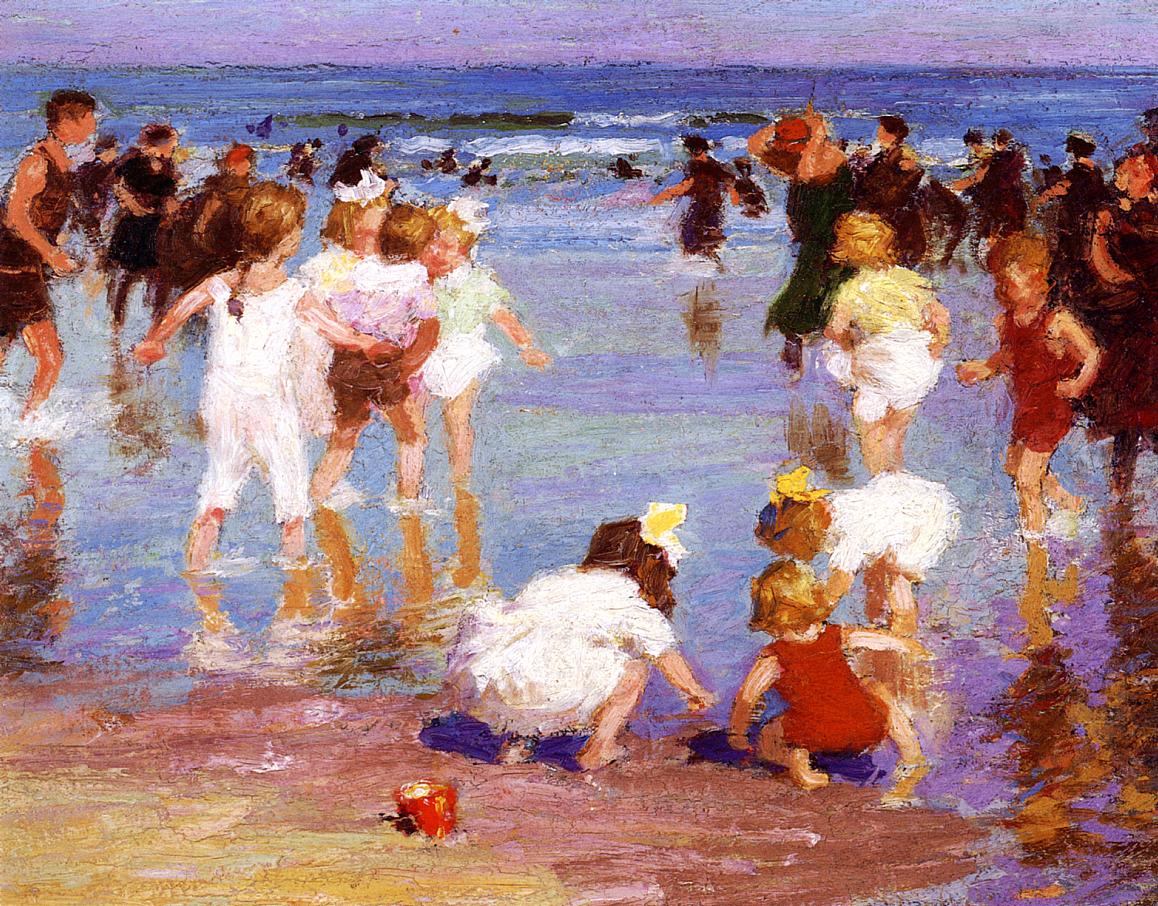

Better yet, Edward Henry Potthast’s beach scenes of women and children and

dads. Notably Happy Days, late

1890s. God isn’t needed for life to be enchanting. That is the message and

insight we get from Raphael, Potthast, and Sheridan. What Sheridan adds is that

that which enchants life must be protected, not just celebrated, because it is constantly

threatened.

In Romans (8:3–4), Paul says, “For what the law was powerless to do because it was weakened by the flesh, God did by sending his own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh to be a sin offering. And so he condemned sin in the flesh, in order that the righteous requirement of the law might be fully met in us, who do not live according to the flesh but according to the Spirit.” Thus, Jesus was born of the sinful flesh of Mary, but conception was miraculous—with God—in the role of dirty old man—impregnating Mary:

In the sixth month the angel Gabriel was sent by God to a town in Galilee called Nazareth, to a virgin engaged to a man whose name was Joseph, of the house of David. The virgin’s name was Mary. And he came to her and said, “Greetings, favoured one! The Lord is with you.” But she was much perplexed by his words and pondered what sort of greeting this might be. The angel said to her, “Do not be afraid, Mary, for you have found favor with God. And now, you will conceive in your womb and bear a son, and you will name him Jesus....” Mary said to the angel, “How can this be, since I am a virgin?” The angel said to her, “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; therefore the child to be born will be holy; he will be called Son of God.... Then Mary said, “Here am I, the servant of the Lord; let it be with me according to your word.” Then the angel departed from her. (Luke 1:26-38)

Clearly,

Mary isn't thrilled about being impregnated by God. (The idea of a god impregnating a human woman was probably adopted from Greek mythology that has Father Zeus impregnated a number of human females, including Alcmene, Antiope, Callisto, Danae, Europa, and Lamia.) This incident was repeated

endlessly by kings/lords to servant girls, and they could use the biblical passage to

justify their sexual aggression. Mary does her duty. She is treated as a tool